Trump's AI Choice: Compete or Control?

The critical risk excessive tariffs and export controls pose to America's AI edge

The moment Donald Trump was declared president-elect, questions about the future of AI policy immediately began to swirl. Armed with majorities in the Senate (and probably the House) and considerable executive powers, Trump will have significant leeway to pursue his policy agenda. For the field of AI, his choices could prove profound. When a technology is just budding, the chances of future “butterfly effects” from poor policy choices are particularly strong. The reverberations from Trump’s election will be felt for decades, not just for the next four years. We must get this right. In my view, trade and geopolitical competition are by far the policy domains most critical to long-term American AI success and should be kept in sharp focus by the new administration.

Begin with trade. Unburdened commerce and easy foreign market acess will be the key to driving forward growth and resulting research investments. Silicon Valley’s AI innovation is built on the legacy and sustainable revenues of past international market dominance. After years of exporting our operating systems, applications, cloud technology and other innovations, we have amassed the research capital needed to do big things. This pattern must continue. To sustainably lead in AI, we must lead in AI trade.

In the competition between the United States and its geopolitical adversaries, our AI prowess has the potential to be a powerful differentiator. Intelligence analysis driven by LLMs, real-time cyber-attack monitoring, automated supply chains, and AI-equipped drones are the key to an effective national defense policy. If our nation’s liberal democratic model is to succeed against its illiberal, antidemocratic or authoritarian competitors, innovation mustn’t fall behind.

As the administration maps out its trade and foreign policy, what strategy should guide decisions? What policy choices should be made?

Focus on Competition

First, the new administration must embrace an emphasis on competition, not control. Meeting the twin goals of building a booming AI sector and besting China depends not on how well we can protect sensitive intellectual property nor on the size of our public investments.1 It’s about whether we can cheaply and effectively sell AI tech abroad.

If our AI exports are strong, the resulting revenues will drive further innovation and help secure a durable economic edge on our competitors. Likewise, leadership in AI exports will minimize the security negatives of Chinese tech influence: If other nations are using our tech, they won’t be using China’s.

To put this competition into policy action, the administration must carefully consider its two most impactful trade levers: tariffs and export controls.

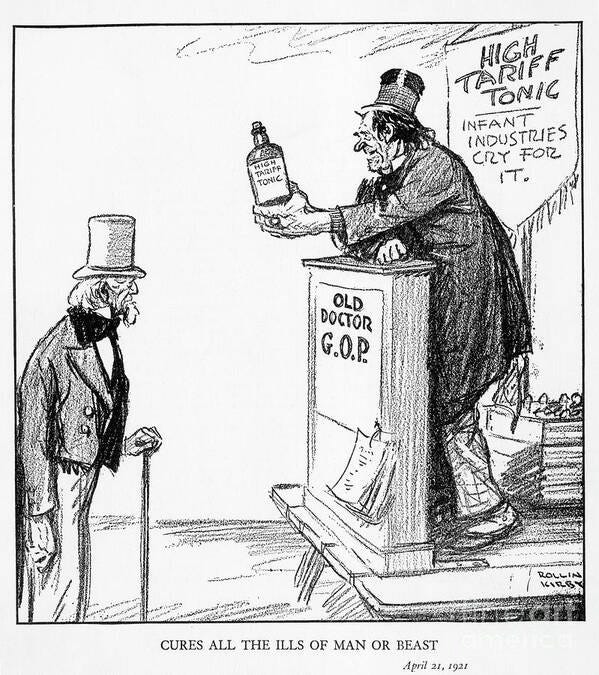

Tariffs

On the campaign trail, candidate Trump was a vigorous advocate of increased general tariffs ranging from 10 percent to several hundred percentage points or more. While some assume approval from Congress might be required for any tariff increases, this view is misguided; existing law, in fact, enables swift presidential action on tariffs.

Tariffs could absolutely make or break the United States’ ability to invest in, make use of, and compete with artificial intelligence. Contrary to common misconceptions, a tariff is a cost imposed not on foreign trade partners but on American companies and consumers. For the AI industry, a general tariff means cost increases, corporate budget contraction, and a potential tech recession.

In a September 2024 report, UBS, an investment banker, predicted both tech hardware and semiconductors to be among the top four sectors that would be hardest hit by a general tariff. Their analysis is spot on. Many of the hardware components that make AI and digital tech possible rely on imported materials not found or manufactured in the United States. Neither arsenic nor gallium arsenide, used to manufacture a range of chip components, have been produced in the United States since 1985. Legally, arsenic derived compounds are a hazardous material, and their manufacture is thus restricted under the Clean Air Act. Cobalt, meanwhile, is produced by only one mine in the U.S. (80 percent of all cobalt is produced in China). While general tariffs carry the well-meaning intent of catalyzing and supporting domestic manufacturing, in many critical instances involving minerals, that isn’t possible, due to existing regulations and limited supply. Many key materials for AI manufacture must be imported, and tariffs on those imports will simply act as a sustained squeeze on the tech sector’s profit margins.

A potential result of tariffs, according to the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, is that":

“[l]owering profit margins may force some businesses with less-flexible budgets—especially small businesses—to lay off workers. But even the companies that do not have to cut jobs would have less funding to invest in building new data centers or to conduct the research and development needed to stay ahead of international competitors.”

The key takeaway: if tariffs lower profits, companies will not invest in the R&D needed to fund competitive, cutting-edge defense technology. Today most AI research investments are handled by the private sector’s proven ability to yield non-stop innovation and breakthroughs. By constraining that capacity, our innovation will lag, if not cease altogether.

For China, the imposition of new tariffs represents a generational leapfrog opportunity. Excessive tariffs could enable Chinese firms to rapidly sweep international markets, dominating global tech, including AI, with superior, cheaper products. During the first Trump administration, China’s rapid dominance in global 5g deployment prompted grave security threats that proposed policy solutions have yet to mitigate. A similar outcome this time around is likely under broad, mistargeted tariffs.

While narrow tariffs would be better than the proposed general tariff, it’s important to recognize that even with limited scope, tariffs could still place unintended burdens on the tech sector. According to an International Trade Comission report on existing aluminum, steel, and Chinese import tariffs, the impact on the tech sector has been a significant 4.1% price increase on semiconductor technology, and a small, yet meaningful 0.8% price increase on the computer equipment and electronic product manufacturing sector. Even tailored measures can yeild meaningful impact.

The president-elect is certainly entering office with a mandate to impose new tariffs. If implemented poorly, however, U.S. chances for future economic and strategic geopolitical success could be in jeopardy. In the coming months, I urge a judicious, tailored, thoughtful approach. As Trump’s team designs new tariff policies, they should take a hint from my fellow Mercatus scholar Christine McDaniels’ general advice: be clear about what you want, make sure affected domestic industry has a plan to adapt to global markets, and team up with key trading partners.

Export Controls

A close policy cousin of tariffs are export controls. While not at the center of the Trump campaign agenda, export controls have been embraced by both parties as a powerful tool to contain China’s tech ambitions. During the first Trump Administration, narrow controls targeted Huawei Technologies, a Chinese tech conglomerate, to check their 5G and IT hardware ascendance. Used then, export controls are likely to color this administration’s efforts to contain China’s AI progress .

Narrow, targeted export controls absolutely have their place in geopolitical competition. If a company is directly funneling American tech to the Chinese military, we should stop them. While no control will completely deny tech to a sufficiently motivated bad actor, the added costs inherent to subversion can slow and inhibit malign ambitions.

Still, success demands judicious application. Unfortunately, current AI export controls can hardly be considered narrow or targeted. Under the Biden Administration, we have seen successive waves of AI-related hardware controls now limiting exports to an unwieldly list of 43 countries that includes even such allies as the United Arab Emirates. This group of countries represents 25% of the global economy.

With such substantial controls, competitive risks abound. According to Interconnect's Kevin Xu, the round of AI hardware controls implemented in 2023 resulted in questionable outcomes. Rather than deny Chinese companies certain critical tech, some of the measures simply prompted a one-to-one reshuffling of contracts from NVIDIA direct to China’s Huawei. The result: rather than deny tech to China, we denied sales to NVIDIA.

This episode illustrates the risk of excessive export controls. By trying to contain China, we risk inadvertently containing our own competitive ambitions.

Once President Trump enters office, I recommend a reassessment of these exsisting controls. The White House should consult with industry, assess the competitive cost burdens, and attempt to empirically weigh those costs against known benefits. In cases where “the juice is worth the squeeze”—keep the controls. Elsewhere, consider rolling restrictions back.

When it comes to possible new controls, I again urge a conservative approach. Export controls on consumer-grade or open-source AI software like some have suggested in the House should be avoided. “Intangible goods,” that is non-physical data, information and algorithms, like software are too difficult to track and control. Software can be smuggled invisibly, copied infinitely, and shared effortlessly. Our trade perimeter is simply too porous for any such export regime to manage and not worth the massive industry burdens. Meanwhile additional hardware controls should only be implemented if there is a clear and present threat, a specific policy outcome in mind, detailed plans made, and enough resources and allies on hand to ensure success.

Conclusion

The best path forward to both geopolitical and economic success is competition, not control. Tariffs and export controls are truly awesome executive powers and therefore demand careful consideration and assessment. Trump is taking office at a critical technological moment. If his administration chooses a steady trade and geopolitical competition policy, the U.S. could seize the moment and secure economic, security and technological returns that will pay dividends for decades to come.

Let’s not squander this opportunity.

These things certainly matter, and will form a part of any policy mix, but trade is the key variable.